- Light sources (light bulbs, lanterns, etc.): ideas that could help you get through the difficult times

- Switched off TV screen with headphones over it: the feeling of emptiness

- Guns, glasses and the helmet: self-defense mechanisms

- Male and Female characters: your body (male character) and your soul (female character)

The Proof Course: Lecture 2

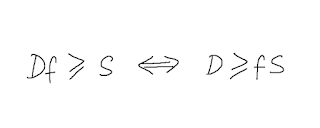

Many real-life situations lead us to considering a mathematical problem dealing with finding all possible numbers \(x\) satisfying a certain formula. In most primitive cases, this formula is an equation involving basic arithmetic operations (like the one we considered in Lecture 1). As an example of a formula that does not fall in this category, consider the following one:

\(x<y^2\) for every value of \(y\) (Formula A)

In other words, the formula expresses the property that no matter what value of \(y\) we pick, we will always have \(x<y^2\). Let us write this purely symbolically as follows (so that it looks more like a formula!):

\(y\Rightarrow x<y^2\) (symbolic form of Formula A)

In general, the symbol "\(\Rightarrow\)" describes logical implication of statements. Here the implication is: if \(y\) has a specific value then \(x<y^2\). In the symbolic form above, the assumption that \(y\) has a specific value is expressed by just writing \(y\) on the LHS (left-hand-side) of the implication symbol "\(\Rightarrow\)". Since we are not giving any further detail as to which specific value does \(y\) have, the implication must not be dependent on such detail, and hence the RHS (right-hand-side), \(x<y^2\), must hold for all values of \(y\). Note however that this type of symbolic forms, where variables are allowed to be written on their own like in the LHS of the implication symbol above, is not a standard practice. We will nevertheless stick to it, as it makes understanding proofs easier.

So, what is the solution of Formula A? If \(x<y^2\) needs to hold for every value of \(y\), then in particular, it must hold for \(y=0\), giving us \(x<0^2=0\). This can be written out purely symbolically, as a proof:

- \(y\Rightarrow x<y^2\)

- \(x<0^2\)

- \(x<0\)

- \(x<0\)

- \(y\Rightarrow 0\leqslant y^2\)

- \(y\Rightarrow x<y^2\)

- \(y\Rightarrow x<y^2\)

- \(x<0^2\)

- \(0^2=0\)

- \(x<0\)

The Proof Course: Lecture 1

In this blog-based lecture course we will learn how to build mathematical proofs.

Let us begin with something simple. You are most likely familiar with "solving an equation". You are given an "equation", say \[x+2=2x-3\] with an "unknown" number \(x\) and you need to find all possible values of \(x\), so that the equation holds true. You then follow a certain process of creating new equations from the given one until you reach the solution: \[2+3=2x-x\] \[5=x\] This computation is in fact an example of a proof. To be more precise, there are two proofs here: one for proving that

if \(x+2=2x-3\) then \(x=5\) (Proposition A),

and the other proving that

if \(x=5\) then \(x+2=2x-3\) (Proposition B).

The first proof is the same as the series of equations above. The second proof is still the same series, but in reverse direction. The two Propositions A and B together guarantee that not only \(x=5\) fulfills the original equation (Proposition B), but that there is no other value of \(x\) that would fulfill the same equation (Proposition A). It is because of the presence of these two proofs in our computation that we can be sure that \(x=5\) is indeed the solution of the equation \(x+2=2x-3\).

In general, a proof is a series of mathematical formulas, like the equations above. However, in addition to a "vertical" structure of a proof, where each line displays a formula that has been derived from one or more previous lines, there is also a "horizontal" structure, where each line of a proof has a certain horizontal offset. This is, at least, according to a certain proof calculus formulated by someone by the name of Fitch. There are other ways of defining/describing proofs; in fact, there is an entire subject of proof theory, which studies these other ways. We will care little about those other ways and stick to the one we started describing, as it is closest to how mathematicians actually compose proofs in their everyday job.

So where were we? We were talking about "vertical" and "horizontal" structure of a proof. Not to complicate things too much at once, let us first get a handle on the vertical structure of proofs, illustrating it on various example proofs that have most primitive possible horizontal structure. We will then, slowly, complexify the horizontal structure as well.

For Proposition A, the proof goes like this:

- \(x+2=2x-3\)

- \(2+3=2x-x\)

- \(5=x\)

The numbers at the start of each line are just for our reference purposes, they do not form part of the proof. Line 2 is a logical conclusion of Line 1: if \(x+2=2x-3\) then it must be so that \(2+3=2x-x\), since we could add \(3\) to both sides of the equality and subtract \(x\) as well – a process under which the equality will remain true if it were true at the start.

Line 3 is (again) a logical conclusion of Line 2: since \(5=2+3\) and \(2x-x=x\), so if the equality in Line 2 were true then the equality in Line 3 must be true as well.

A series of lines of mathematical formulas where every next line is a logical conclusion of the previous one or more lines, is a mathematical proof with simplest possible horizontal structure. We will call such proofs "basic".

Proposition B also has a basic proof:

- \(5=x\)

- \(2+3=2x-x\)

- \(x+2=2x-3\)

\(x=5\) and \(x+2=2x-3\),

\(x=5\) or \(x+2=2x-3\),

Pure Mathematics: Job Description

The SOFiA Proof Assistant Project

Background

The goal of this project is to build a proof assistant based on the SOFiA proof system, where the capital letters in SOFiA stands for Synaptic First Order Assembler (the purpose of the lower-case "i" will be explained further below). The use of terms "synapsis" and "assembler" is a suggestion of Brandon Laing, who wrote an MSc Thesis, "Sketching SOFiA" (2020), where the notion of an assembler was introduced: an assembler is the monoid of words in a given alphabet, seen as a monoidal category. The main result of his MSc Thesis was a characterization of assemblers using intrinsic properties of a monoidal category. An assembler gives a robust theoretical framework which guides the syntactical structure of the SOFiA proof system. The latter has been refined through a series of discussions with Louise Beyers and Gregor Feierabend in 2021, after which the first computer implementation of the SOFiA proof system was produced, based on the Python programming language. You can learn about it here. In January 2021, Gregor Feierabend developed a self-contained Haskell implementation, with user interface and documentation, which can be accessed here.

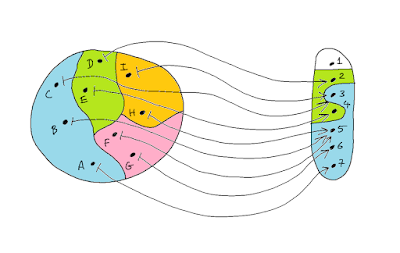

Overview of the SOFiA Proof System

- Making an assumption (no restrictions except that the assumption must be a valid SOFiA expression).

- Restating an already stated SOFiA expression.

- Recalling a theorem or an axiom, external to the proof.

- Equating a stated SOFiA expression with itself.

- Synapsis: stepping out of an assumption block (this allows to conclude quantified statements, as well as implications).

- Application a SOFiA expression (this allows to conclude from quantified statements as a generalization of the modus ponens rule).

- Substitution: substituting SOFiA expressions within each other based on already stated equalities.

These deduction rules do not include rules for disjunction or fallacy. The latter can be implemented as axiom schemes. So at its base, the SOFiA proof system embodies a bit less than intuitionistic logic. This is marked by the appearance of lower-case "i" in "SOFiA". Note however that because in the SOFiA syntax there is no distinction between "objects" and "statements about objects", the SOFiA proof system is not quite the same as the usual proof system of a first-order logic, although in a loose sense SOFiA does have the structure of a first-order language. One of the key differences with standard first-order languages is that in SOFiA one does not introduce additional relational or functional symbols. Instead, one may write any sequence of allowed characters in SOFiA which can be given the intended meaning of a relational or a functional symbol by means of axioms. Possibility for a sound and complete embedding of any first-order logic in SOFiA still needs to be proved and is currently one of the founding themes of PhD research by Brandon Laing.

Developing the Proof Assistant

The current version(s) of the SOFiA proof assistant have the following shortcomings, which are to be addressed in the near future:

- The proofs can only be built line-by-line, it is currently not possible for the computer to fill the missing lines. This applies to both the Python and Haskell implementations.

- The Python implementation source code is messy and there is currently no documentation.

- The Haskell implementation contains bugs.

- There Python implementation does not have a user interface.

- Python and Haskell implementations come with modules for Boolean Logic and Peano Arithmetic, but they do not yet come with a module for Set Theory.

Bracket Notation for Mathematical Proofs

The bracket notion for mathematical proofs is an adaptation of the Fitch notation for Gentzen's natural deduction proof system. It has led to the development of the SOFiA proof assistant. This post brings together some videos explaining the bracket notation and the first-order formal language for mathematics in the context of the bracket notation.

1. General Overview

2. Building Blocks for Statements

3. Examples of Forming Statements

4. Examples of Forming Statements (Continued)

5. Concluding Quantified Statements

6. Concluding from Quantified Statements

Category Theory 2022 - an NGA course

Here you will find the content for the Category Theory course given under the National Graduate Academy NGA-Coursework of the CoE-MaSS. The lectures are on Saturdays 9:00-11:00.

Register here to receive the Zoom link for joining the lectures

There is also a Discord channel for this course, which you can find on the Discord server of the NGA-Coursework project.

This is a video-based course aimed at post-graduate students and as well academics interested to learn about category theory, with live participation of the audience shaping the content of the course. For a reading course at the South African honors level, see:

- Category Theory: A First Course by George Janelidze

- Elementary Introduction to Category Theory by Amartya Goswami and Zurab Janelidze

Lecture 1: Categories

Lecture 2: Functors

Lecture 3: Natural Transformations

Lecture 4: Adjunctions

Lecture 5: Limits

Lecture 6: Duality

Lecture 7: Yoneda Embedding

Lecture 8: Equivalence of Categories

Mathematical Structures Course 2022

Elementary Introduction to Set Theory

This is the blog post of the 2022 August NITheCS Mini-School. Let us begin with some useful links:

- Lecture notes on universes of sets (introductory)

- Some videos explaining the concepts from the lecture notes above

Lecture 1

Lecture 2

Lecture 3

Lecture 4

Guitarist, Contemplation and Camille

Guitarist

This picture symbolizes a human state when one is working on a routine task, while one's mind looks into the bigger picture of things. While guitarists hands are busy playing on the guitar, his eyes are looking into the open space from a balcony. The fence of the balcony symbolizes the restrictions imposed on us by the necessity of a routine task.

Contemplation

This picture shows the back of a woman with yellow hair, in a stylish red dress, gazing at the white moon. The hair is blowing in a light wind. Mountains covered in snow are in the background. Her outfit is certainly not a match for the cold weather, but contemplation will keep her body warm. This picture symbolizes that deeper things in life can give us physical strength.

Camille

Waves

This freehand digital artwork represents the idea that significant change requires restructuring of foundations. The solid ground on the right middle side of the picture (the foundations) dissolves into an uproar of waves that illustrate the process of restructuring, which may appear to be chaotic. Going back from the left to the right side of the picture the waves subside into (new) foundations.

Beautiful Roses (opus 1601)

- The bud with the sun in the background shown at the start of the video represents an idea that starts the creative process.

- The rose opening up, which is repeated three times in the video, represents the anticipation of the fulfillment, the fulfillment, and the reflection on the fulfillment of the creative process.

- The first character, dressed in conservative clothes, symbolizes the mind. The second character symbolizes the soul. The first character is reserved in her display of emotions as well as in her interaction with the roses. The second character is spontaneous and emotional, who interacts more intimately with the roses and displays enjoyment in such interaction. These represent the rational approach of the mind and the contrasting intuitive approach of the soul in a creative process.

- The first character wears black top throughout the video. The second character wears brighter tops. The first represents the critical approach of the mind and the struggles of the creative process, while the second represents the positive approach of the soul and the joy of the creative process. The positive/critical disposition of the soul versus the mind is symbolized also in the brighter lighting background for the second character versus the first character.

- For the most part of the video the character representing the mind has roses separated in bottles in the foreground. This represents the attitude of the mind to concentrate on the details in isolation from each other. The character representing the soul is, in contrast, shown with a bucket of flowers. This symbolizes the holistic approach of the soul in the creative process. The single flower that the second character appears to have isolated from the bucket symbolizes the driving idea behind the creative process.

- At the end of the video, the flowers in front of the character representing the mind are no longer separated in their bottles. Instead they appear lying in a heap in front of her, with one flower from the heap in her hands. This represents the conclusion of the creative process, when the mind dismisses the details and brings them all together, leading to the emergence of the contour of the bigger picture as a detail of its own.

- Just before the last scene, the character representing the soul passes the single rose she is holding towards the screen. This symbolizes disengagement of the soul at the end of the creative process. In the final scene, however, the other character remains with the roses. For the first time here, she smiles, but momentarily, while smelling the flower she is holding. This symbolizes that what remains after conclusion of the creative process is just mental image of what has been created. The excitement has subsided and there is only one emotion left, the unique positive experience of the mind in the process, which lasts only for one moment, making that moment worth the creative process: the feeling of accomplishment.

Reverse Prime Composite Numbers

The Transition from High School Mathematics to University Mathematics

These are notes in progress for a talk given at the online user group conference of the advanced programme mathematics organized by ieb (19 February 2022)

1. Introduction

2. Misleading Questions

3. Factual Teaching vs Insightful Teaching

- "sketch" instead of "graph" (or "sketch of the graph").

- Wilson says "-3 is not included" (it is rather the paint (-3,-1) that is not included in the graph) but "4 is included" (similarly, 4 is merely the x-coordinate of the point included in the graph).

- Wilson says that the domain is "where your graph is on the x-axis", and "range is where the graph is on the y-axis".

- Wilson says "if it is not defined, we put a round bracket, if it is defined, we put a square bracket".

6. Final Note ♪

7. Some Feedback from Students

Python-Based Introduction to Mathematical Proofs

1. What is a Mathematical Proof?

- discover new mathematical knowledge,

- analyze existing mathematical knowledge,

- verify truthfulness of a piece of mathematical knowledge.

Noetherian information systems

These are notes for a colloquium talk to be given at NITheCS.

The Snake Lemma from this fragment of a 1980 film ("It's My Turn", starring Jill Clayburgh and Michael Douglas), along with many other similar theorems in abstract algebra, known to be true for a variety different algebraic settings, can all be established in a unified setting of noetherian forms. This post attempts to give a preliminary step towards a possibly ambitious goal of applying noetherian forms outside abstract mathematics. In this light we propose a variation of this notion, a "noetherian information system", which is intended to be more agile in terms of identifying applications.

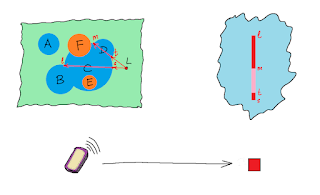

General Information Systems

- If we think of E as the range of possible locations of the cellphone, then E gives more information about the location of the cellphone than C does. We call this the classical interpretation. In this interpretation, E being part of C gets interpreted as E "implying" C in the sense of classical mathematical logic.

- If we think of each possible location as an attribute of the cellphone, then we can interpret E to be a state of the cellphone in which the cellphone has less attributes than in the state C. We call this the quantum interpretation, since with this interpretation, the information cluster E is seen as a state where the cellphone is simultaneously in all locations within the region E.

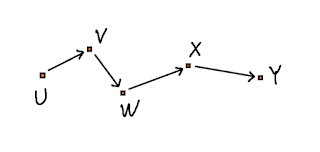

Inputs and Outputs

- Any transmission with the same target as that of the input, whose every reach is a reach of the input, arises as a composite of the input transmission with a transmission to the source of the input.

- The input transmission maps clusters injectively (i.e., different clusters do not transmit to the same cluster).

- Any cluster that is part of a reach of the input transmission is itself a reach of the input transmission.

- Any transmission with the same source as the output, whose every non-stash is a non-stash of the output, arises as a composite of the output with a transmission from the target of the output.

- If the output transmission maps a cluster B to part of a clusters A, and all stashes are part of A, then B is part of A as well.

- Any cluster in the target of the output is a reach of the output transmission.

- Any transmission decomposes as an output transmission followed by an isotransmission and followed by an input transmission.

- For any two inputs there is a third input whose reaches are precisely those clusters which are reaches of both initial inputs.

- For any two outputs there is a third output whose stashes are precisely those clusters which are parts of every single cluster containing all stashes of both initial outputs.

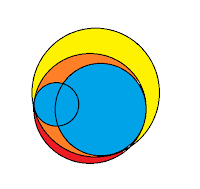

Mathematical Examples

Topological Information Systems

- The first information system is not topological since clusters there are always circular regions of a plane. It is impossible to superpose two circular regions into another circular region. Note that a superposition of a set S of clusters is formally defined as a cluster J such that every member of S is part of J and moreover, J is part of any other cluster K that has the same property (i.e., that every member of S is part of K). So superposition of two disks should be a disk which contains both, but which is contained in any other disk containing both. Such disk does not exist unless one of the two disks contains the other: on the illustration below, an attempt to superpose two blue disks must produce a disk that wholly lies both in the yellow disk and the red disk, i.e., that lies in the orange region, while at the same time contains both blue disks -- this is not possible.

- Although non-zero finitely many closed intervals can be superposed, infinitely many, in general, cannot be superposed.

- In both cases, empty superposition is not possible.

- the smallest cluster is transmitted to the smallest cluster, and

- superposing clusters in the source information system and then transmitting the resulting cluster, is the same as first transmitting the initial clusters and then superposing them in the target information system.

- Reverse transmission is monotone and it preserves meets of clusters (a meet of a set of clusters is defined as the largest cluster that is part of each cluster).

- Transmission followed by reverse transmission results in expansion of the cluster.

- Reverse transmission followed by transmission results in shrinking of the cluster.

- Transmission, then reverse transmission, and then transmission again, results in the same cluster as by initial transmission. There is a similar property starting with reverse transmission in the place of transmission.

Concluding Remarks

- Is there a useful real-life interpretation of a noetherian information system?

- If yes, does it lead to the ability to usefully model real-life information systems as noetherian information systems?

- In particular, are there any applications in machine learning or data science?

- Or, is it perhaps possible to use noetherian information systems to usefully model function of a living organism, or maybe, cognitive function of a human being?

- Does the category of Hilbert spaces, which is neither an abelian nor a semi-abelian category, but which plays an important role in quantum mechanics, have a noetherian form?

- Can the physical universe be modelled as a noetherian information system?